What is the name of the piece that you have in Grabbed? Kidnapped Girls What was the inspiration for your piece? What compelled you to write it? I was inspired by the 2014 kidnapping of school girls in Nigeria by the terrorist group Boko Haram. I thought of the incident described in my poem, and of the book All I Really Need to Know I Learned in Kindergarten, and realized that the facts of life as a female in this world had always been clear to me. When I was in kindergarten, and the neighborhood boys formed gangs to sexually menace girls, this was simply what happened, with none of us kids knowing or questioning why. Luckily, it was harmless, literally only child’s play, but was our game some kind of inborn practice for the future? My grandmother seemed to think so. I saw what happened in Nigeria, what happens all over the world, as the adult version of my childhood experience, and wanted to convey that feeling. I have spent my life wondering, but still don’t know, why we played these games, where the idea came from. My grandmother only wanted to keep girls pure, free from pregnancy and shame, until they could be safely married. I was afraid of her anger as a child, but now saw her power to shout NO to sex in a new light. Saying no could be truly protective, not merely policing, of women. Used for the right purpose, a wrathful voice like Grandma’s could be used to shame rapists and kidnappers and should be. I wanted the force of her sound waves to be able to stop Boko Haram. What compelled you to submit your work for this anthology? Was it a difficult decision? The decision was not at all difficult. I learned of the anthology through my poetry teacher Ellen Bass and was happy to have the opportunity to submit. My poem had previously been accepted, but not yet published, by a wonderful journal which unfortunately had to cease publishing. When I heard of the Grabbed anthology I was excited to think my poem might find another poem there. It seemed like the perfect place. I was also thrilled that Joyce Maynard and my heroine Anita Hill were participating in the book. I was still burning about the Anita Hill hearings and ever will be. Why did you choose this particular form or genre for this piece? My first impulse is usually toward poetry. I like trying to say as much possible with the fewest words. That said, I also like attempting essays. Can you speak to the evolution of writing your piece? How long did it take you to write this piece, including revision? I was asked to do a partial revision by the editor of the journal that first accepted the poem. She helped me with the process. Later, I made a few more changes before submitting it to the anthology. So the whole process took several years, but was not continuous. As a writer, do you feel obliged to share difficult experiences? Why? Yes. Because the sound and light of words are needed to dispel the silence and darkness of secrecy and trauma. My poem in this anthology is more collective than personal in feeling, but I know how hard it can be to share experiences that are traumatic even to think about. Overcoming the resistance to re-experiencing the trauma becomes part of the difficulty of writing. What do you feel the impact of the #MeToo movement has been on your work, if any? The #MeToo movement has been yet another affirmation, and the strongest yet, of the universality of some of my/our experiences and their need to be shared to bring about collective change. I know from experience how long this can take. I read The Second Sex when I was twelve, came of age in the ‘60s, experienced second-wave feminism in the ‘70s, followed by Phyllis Schlafly and the sad recession of the wave, then a resurgence of the wave with the Anita Hill hearings, and now another with this movement. History progresses in waves and although our bodies don’t evolve, culture can. The struggle of women is as old as humanity, in part because for women to be free men must also be free. Unless that’s vice versa! Also, generations are short and much gets forgotten that must be rediscovered to be remembered. And youth thinks differently than age, yet age only makes me feel my youthful thoughts more deeply. If historical movements proceed in waves, participating in one as a writer is like helping to build a cathedral. My or your story may be remembered or it may not. But while it is read it has a chance to affect another life directly, and that is what builds the cathedral. Anyone who wants to tell a MeToo story should find a way to do it. The material will not be wasted. What would you say to another writer who has been uncomfortable or silent about their experience? How can they begin to share their experiences? Joining a writer’s group led by a skilled writer/teacher can be a great way to start sharing experiences safely. The leader should understand the nature of your experiences and the special difficulties of writing about them. All personal experiences are difficult to write about in a way that reaches the reader, but some more than others. Trauma is famous for wishing to stay hidden. If your experiences have been very traumatic, and you have not yet done so, you might also consider seeing a therapist. You can read books like Gregory Orr’s Poetry as Survival, Tillie Olsen’s Silences, Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own, to name some classics. There are many more. You can journal just for yourself and remember that you are not alone. This becomes evident as soon as you open your mouth. Others join you. But it does take courage to start. It is scary yet a privilege to be able to speak. We are lucky to have more opportunity now than ever before. How can a publication such as Grabbed help to empower or heal readers? By validating readers’ experiences. By showing readers they are part of an already huge and powerful crowd. By giving them permission to keep moving forward. Catherine Gonick’s poetry has appeared in literary magazines including Notre Dame Review, Beltway Poetry Quarterly, Lightwood, Forge, Sukoon, and PoetsArtists, and in anthologies including in plein air, and forthcoming, Poemas Antivirus. She was awarded the Ina Coolbrith Memorial Prize for Poetry and was a finalist in the National Ten-Minute Play Contest with the Actors Theatre of Louisville. She is part of a company that mitigates the effects of climate change.

0 Comments

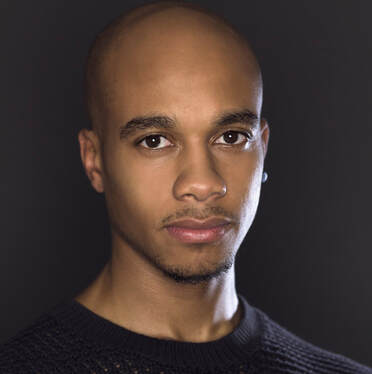

What is the name of the piece that you have in Grabbed? Blindsided Can you speak to the evolution of writing your piece? I have been writing about sexual abuse for decades –sexual harassment in the workplace, violence against women in film, forced childbirth, sexual abuse and assault across religious denominations, especially in the church of my childhood, the Catholic Church. I’ve written and published many personal essays--about having had breast cancer, struggling with an eating disorder, the impact of the Catholic Church’s misogyny on my sense of self, my sexuality, my body. But not until publishing my essay “Blindsided” in Grabbed have I revealed this experience of sexual assault and its aftermath. “Blindsided” is excerpted from a collection of essays, a memoir in progress about my awakening as an Italian-American, working-class, second-wave feminist. The piece is neither new nor newly written. But the experience of seeing it out there in the world is new. Unlike my journalism and other personal essays, this essay represents a different order of revelation and vulnerability. While recalling the experience that is the subject of this essay has always stirred shock, bewilderment, and anger in me, not until I saw “Blindsided” in this collection did I feel what I have never really felt before—sadness. It is a deep, universal sadness, a sadness that very much matches the moment, when at last, the larger culture is willing to acknowledge the harm done, which is the only way that change will ever come. What would you say to another writer who has been uncomfortable or silent about their experience? How can they begin to share their experiences? For anyone who has been grabbed, assaulted, raped, or abused and kept that locked inside, please talk to someone you trust. Share the experience. Work through it. Don’t be afraid of it. By all means, write about it. But as to publishing your experience, I do not think that is an action best done on impulse. Let the idea of going public germinate. That’s not because you should not publish your experience, not at all. It is because you cannot predict the response. Not everyone in your world—family, friends, colleagues, strangers--may support you. You need to be prepared, to know where you will go for solace and comfort. But if you do find the courage to share what happened, know that you will be helping to decimate the notion of the ordinariness of being “grabbed.” You will be helping to end the shame heaped upon the targets of that abuse instead of on the perpetrators. And your voice will be part of a growing worldwide chorus—you will not be alone. How can a publication such as Grabbed help to empower or heal readers? The sheer volume and power of the voices in this unique anthology provide a dramatic example of how normalized both sexual assault and the silence surrounding sexual assault have been in American culture, and how crucial it is that the normalization and the silence end, not just in the U.S., but all over the world. Angela Bonavoglia, MSW, writes about social, health and women’s issues, politics, film, TV, and all things Catholic. Most recently, she authored Good Catholic Girls: How Women Are Leading the Fight to Change the Church (a Booklist Nonfiction Women’s History Top 10, 2006). Her first book, The Choices We Made: 25 Women and Men Speak Out About Abortion (foreword by Gloria Steinem) features her interviews with celebrities and other prominent people about their abortion experiences (1920s-1980s). Her work has appeared in many venues, including Ms., The Nation, the Chicago Tribune, Salon, Women’s Media Center, Rewire, Medium, and HuffPost. Find her on Twitter @angiebona or at www.angelabonavoglia.com.  What is the name of the piece that you have in Grabbed? “When a White Man Attempts to Steal Your Soul” What was the inspiration for your piece? What compelled you to write it? Back when I used to be a regular at the gym (and, as much as I’d love to blame the fact of COVID making gyms untenable for that no longer being the case, my therapist says being honest about my choices is a great way to combat imposter syndrome), this fascinating thing would happen whenever I entered the steam room. Pretty consistently—and I’m sure this was partly only so consistent because of the specific gyms I frequented (in queer-friendly neighborhoods of New York City)—there’d be a guy or a few lounging inside, cruising for a sexual encounter with someone they didn’t know. I didn’t really have a problem with this so long as consent and boundaries were acknowledged and respected. When they are, the person being cruised usually only notices what’s happening if they are also looking for the encounter—if they return the cruiser’s sideways glance that’s held for mere moments too long, or if they refuse to slide away down the damp wooden bench when the cruiser sits just close enough that the hairs on their legs come within a moth’s sigh of grazing. When consent and boundaries are not respected, however, there is no way not to notice, even if you’re just trying to sweat out the tension after backbreaking exercise. Even if you’re straight. Even if you’re too young. And, unfortunately, this happened far too often, and was the same type of violence even if I was open to a different kind of sexual experience with a different kind of person at the time. I noticed this happening particularly when the cruiser was an older white man. He would usually spend all day in the steam room, a venus fly trap just waiting for his prey. The clientele of the gyms I visited were primarily Black, just like me. I would become so furious when this happened—even if it wasn’t directed at me. It evoked all of the sexual violence I experienced since I was a ten year old boy, violence I no longer questioned as being violence, though it took many years for this type of clarity (shout out again to my therapist). Just like the child I used to be, I always felt so powerless in the face of these steam room predators. All the solutions I could think of always felt wrong. As a Black person, I knew I couldn’t turn to the police and expect them to believe my word over theirs, what to speak of expecting law enforcement to have a response that wasn’t carceral, when carcerality is so central to the pervasiveness of sexual violence in this society in the first place. But it was either the police, running away, or responding the violence myself, which felt equally out of the question, though I didn’t know why. Or rather, the reasons why—that violence is never the answer, that these are things police are supposed to handle—felt woefully inadequate. This essay was me exploring whether those reasons for inaction actually hold up under scrutiny. When, if ever, is a survivor’s violent response to sexual abuse justified? What happens when we allow that there must be a point when it is? How do the answers to these questions intersect with the history of racial and gender-based oppression, and what responses are deemed appropriate to those things as well? Can you speak to the evolution of writing your piece? How long did it take you to write this piece, including revision? I had the idea to write the piece after one particularly disgusting experience where I literally had flashes of myself killing the predator in the steam room, but instead I just walked out. In the face of this inadequate response, my body retaliated, and I nearly had a panic attack on the walk home. I process my social anxiety through my writing, and writing through what was happening to me and trying to make sense of it felt natural. I pitched the piece to a friend who worked as a junior editor at a fairly well-known literary magazine, and she loved it. The first draft I sent her was admittedly awful. I was still trying not to say what I knew needed to be said, what my panic-stricken body was telling me that I really wanted to say, but my friend was so gentle and sensitive, which I so appreciate. She asked to get coffee to talk about revisions, encouraged me to push further into my honest feelings and away from vague generalities and cliches around sexual violence I’d ran away into, and eventually I got closer to a piece that felt honest and truthful. At that point—and, I would say, relatedly—my friend couldn’t get approval for publication from her bosses, and she eventually killed the piece. Usually, the things that ease my anxieties, especially around issues like sexual violence, are the same things others find inconceivable. I did some more revisions and then pitched it to an editor at the New York Times, who really liked it as well. I had never written for the publication before, and it was such a different process than what I was used to. After her initial interest, I would follow up every few weeks and she would let me know she was still trying to find a date for it. After about two months, she admitted that she didn’t think she’d ultimately be able to get approval to publish either. Finally, I pitched it to the (now defunct) queer publication, INTO, and they ran it pretty much as was. This was about six months after I started the piece. It’s important to note that all the editors who showed initial interest were Black, but only at INTO did the Black editor have final say. It’s important because, if violence in response to oppression is on the table, non-Black people have much more at stake. When Richard Blanco’s people reached out to my agent about Grabbed, submitting the piece made sense. The project seemed guided by a credo of the importance of uncomfortable truths in the face of sexual violence—a credo that isn’t widely shared in a patriarchal society, but that is necessary. I’m so glad the piece ultimately found a home here. As a writer, do you feel obliged to share difficult experiences? Why? I feel obliged to share difficult experiences only in the sense that, usually, writing through difficulties is how I find the answers I’m seeking. When people ask for whom I am writing, the answer is almost always “me.” That’s not to say that I don’t consider anyone else’s perspective, or that I write things like this without any concern for helping other people. But I have found that the best I can do for others always comes from knowing myself, knowing my limitations, strengths and weaknesses; and the best way I can come to know myself is by writing honestly to myself and sharing that writing with others whom it can possibly help too. But it’s not for (or only for) others. That distinction is important because when you feel obligated to write for others only, or even centrally, you can sacrifice yourself in ways that are detrimental to everyone. You write about things you have no expertise or investment in. You don’t find the answers you are looking for because it’s not about what you are looking for at all. You make yourself vulnerable to horrible things without any necessary protections in place. So, I’d like to think I wouldn’t have ever written something this difficult until I was ready for it. Until I knew what answers I was seeking and until I had the weapons to make the journey to them safely. By the time the piece was rejected, I was completely okay with that. I did not question its usefulness or my skills. Because I didn’t feel obligated to the people who made those decisions, or anyone who might share their judgment. What would you say to another writer who has been uncomfortable or silent about their experience? How can they begin to share their experiences? I would reiterate what I said above: share your experience for yourself. You have a right to find the answers you are seeking, even if it makes others uncomfortable, but you do not have to pretend to have the answers if you don’t, if it makes you unsafe. I would share what my therapist taught me: being honest about your choices is a great way to manage your anxieties. Everybody is not going to like you sharing your truth, but those who are supposed to hear it will. Everybody won’t think it’s publishable, but those who know better exist. Do it with them in mind. There are so many more of us than they make it seem. Writing for yourself, and others like you, is okay, is worthy, is a glorious thing. And that is because you are a glorious thing. Hari Ziyad is a cultural critic, a screenwriter, the editor-in-chief of RaceBaitr, and the author of Black Boy Out of Time. They are a 2021 Lambda Literary Fellow, and their writing has been featured in BuzzFeed, Out, the Guardian, Paste magazine, and the academic journal Critical Ethnic Studies, among other publications. Previously they were the managing editor of the Black Youth Project and a script consultant on the television series David Makes Man. Hari spends their all-too-rare free time trying to get their friends to give the latest generation of R & B starlets a chance and attempting to entertain their always very unbothered pit bull mix, Khione. For more information about the author, visit www.hariziyad.com. |

Grabbed BlogHave a blog idea for us? Submit it here. Archives

October 2020

Categories |

|

BUY GRABBED

|

If you or anyone you know is a victim of domestic violence, please call The National Domestic Violence Hotline: 1-800-799-7233 1-800-787-3224 (TTY) En Español: 1.800.799.7233 |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed