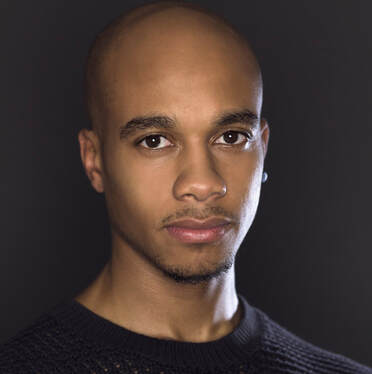

What is the name of the piece that you have in Grabbed? “When a White Man Attempts to Steal Your Soul” What was the inspiration for your piece? What compelled you to write it? Back when I used to be a regular at the gym (and, as much as I’d love to blame the fact of COVID making gyms untenable for that no longer being the case, my therapist says being honest about my choices is a great way to combat imposter syndrome), this fascinating thing would happen whenever I entered the steam room. Pretty consistently—and I’m sure this was partly only so consistent because of the specific gyms I frequented (in queer-friendly neighborhoods of New York City)—there’d be a guy or a few lounging inside, cruising for a sexual encounter with someone they didn’t know. I didn’t really have a problem with this so long as consent and boundaries were acknowledged and respected. When they are, the person being cruised usually only notices what’s happening if they are also looking for the encounter—if they return the cruiser’s sideways glance that’s held for mere moments too long, or if they refuse to slide away down the damp wooden bench when the cruiser sits just close enough that the hairs on their legs come within a moth’s sigh of grazing. When consent and boundaries are not respected, however, there is no way not to notice, even if you’re just trying to sweat out the tension after backbreaking exercise. Even if you’re straight. Even if you’re too young. And, unfortunately, this happened far too often, and was the same type of violence even if I was open to a different kind of sexual experience with a different kind of person at the time. I noticed this happening particularly when the cruiser was an older white man. He would usually spend all day in the steam room, a venus fly trap just waiting for his prey. The clientele of the gyms I visited were primarily Black, just like me. I would become so furious when this happened—even if it wasn’t directed at me. It evoked all of the sexual violence I experienced since I was a ten year old boy, violence I no longer questioned as being violence, though it took many years for this type of clarity (shout out again to my therapist). Just like the child I used to be, I always felt so powerless in the face of these steam room predators. All the solutions I could think of always felt wrong. As a Black person, I knew I couldn’t turn to the police and expect them to believe my word over theirs, what to speak of expecting law enforcement to have a response that wasn’t carceral, when carcerality is so central to the pervasiveness of sexual violence in this society in the first place. But it was either the police, running away, or responding the violence myself, which felt equally out of the question, though I didn’t know why. Or rather, the reasons why—that violence is never the answer, that these are things police are supposed to handle—felt woefully inadequate. This essay was me exploring whether those reasons for inaction actually hold up under scrutiny. When, if ever, is a survivor’s violent response to sexual abuse justified? What happens when we allow that there must be a point when it is? How do the answers to these questions intersect with the history of racial and gender-based oppression, and what responses are deemed appropriate to those things as well? Can you speak to the evolution of writing your piece? How long did it take you to write this piece, including revision? I had the idea to write the piece after one particularly disgusting experience where I literally had flashes of myself killing the predator in the steam room, but instead I just walked out. In the face of this inadequate response, my body retaliated, and I nearly had a panic attack on the walk home. I process my social anxiety through my writing, and writing through what was happening to me and trying to make sense of it felt natural. I pitched the piece to a friend who worked as a junior editor at a fairly well-known literary magazine, and she loved it. The first draft I sent her was admittedly awful. I was still trying not to say what I knew needed to be said, what my panic-stricken body was telling me that I really wanted to say, but my friend was so gentle and sensitive, which I so appreciate. She asked to get coffee to talk about revisions, encouraged me to push further into my honest feelings and away from vague generalities and cliches around sexual violence I’d ran away into, and eventually I got closer to a piece that felt honest and truthful. At that point—and, I would say, relatedly—my friend couldn’t get approval for publication from her bosses, and she eventually killed the piece. Usually, the things that ease my anxieties, especially around issues like sexual violence, are the same things others find inconceivable. I did some more revisions and then pitched it to an editor at the New York Times, who really liked it as well. I had never written for the publication before, and it was such a different process than what I was used to. After her initial interest, I would follow up every few weeks and she would let me know she was still trying to find a date for it. After about two months, she admitted that she didn’t think she’d ultimately be able to get approval to publish either. Finally, I pitched it to the (now defunct) queer publication, INTO, and they ran it pretty much as was. This was about six months after I started the piece. It’s important to note that all the editors who showed initial interest were Black, but only at INTO did the Black editor have final say. It’s important because, if violence in response to oppression is on the table, non-Black people have much more at stake. When Richard Blanco’s people reached out to my agent about Grabbed, submitting the piece made sense. The project seemed guided by a credo of the importance of uncomfortable truths in the face of sexual violence—a credo that isn’t widely shared in a patriarchal society, but that is necessary. I’m so glad the piece ultimately found a home here. As a writer, do you feel obliged to share difficult experiences? Why? I feel obliged to share difficult experiences only in the sense that, usually, writing through difficulties is how I find the answers I’m seeking. When people ask for whom I am writing, the answer is almost always “me.” That’s not to say that I don’t consider anyone else’s perspective, or that I write things like this without any concern for helping other people. But I have found that the best I can do for others always comes from knowing myself, knowing my limitations, strengths and weaknesses; and the best way I can come to know myself is by writing honestly to myself and sharing that writing with others whom it can possibly help too. But it’s not for (or only for) others. That distinction is important because when you feel obligated to write for others only, or even centrally, you can sacrifice yourself in ways that are detrimental to everyone. You write about things you have no expertise or investment in. You don’t find the answers you are looking for because it’s not about what you are looking for at all. You make yourself vulnerable to horrible things without any necessary protections in place. So, I’d like to think I wouldn’t have ever written something this difficult until I was ready for it. Until I knew what answers I was seeking and until I had the weapons to make the journey to them safely. By the time the piece was rejected, I was completely okay with that. I did not question its usefulness or my skills. Because I didn’t feel obligated to the people who made those decisions, or anyone who might share their judgment. What would you say to another writer who has been uncomfortable or silent about their experience? How can they begin to share their experiences? I would reiterate what I said above: share your experience for yourself. You have a right to find the answers you are seeking, even if it makes others uncomfortable, but you do not have to pretend to have the answers if you don’t, if it makes you unsafe. I would share what my therapist taught me: being honest about your choices is a great way to manage your anxieties. Everybody is not going to like you sharing your truth, but those who are supposed to hear it will. Everybody won’t think it’s publishable, but those who know better exist. Do it with them in mind. There are so many more of us than they make it seem. Writing for yourself, and others like you, is okay, is worthy, is a glorious thing. And that is because you are a glorious thing. Hari Ziyad is a cultural critic, a screenwriter, the editor-in-chief of RaceBaitr, and the author of Black Boy Out of Time. They are a 2021 Lambda Literary Fellow, and their writing has been featured in BuzzFeed, Out, the Guardian, Paste magazine, and the academic journal Critical Ethnic Studies, among other publications. Previously they were the managing editor of the Black Youth Project and a script consultant on the television series David Makes Man. Hari spends their all-too-rare free time trying to get their friends to give the latest generation of R & B starlets a chance and attempting to entertain their always very unbothered pit bull mix, Khione. For more information about the author, visit www.hariziyad.com.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Grabbed BlogHave a blog idea for us? Submit it here. Archives

October 2020

Categories |

|

BUY GRABBED

|

If you or anyone you know is a victim of domestic violence, please call The National Domestic Violence Hotline: 1-800-799-7233 1-800-787-3224 (TTY) En Español: 1.800.799.7233 |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed