What was the inspiration for your piece? What compelled you to write it? That’s a good question! I can’t really say, to be honest. I do know the poem surprised me with its sudden clarity and shifts in perspective, and I do know I was intrigued by the fact that I didn’t fully understand its situation but instead saw the scene—and the woman—with striking vividness and an ache of truth. For many years, my writing-practice has entailed a few hours at the computer every morning, before I do anything else (except drink coffee), trying to capture something—some line or image or phrase—I can run with, so to speak, without “thinking,” until—if I’m lucky—I arrive somewhere that feels authentic. If I’m working in poetry, this process entails following that initial impulse within the limitations the line—its cadence mostly--imposes on my choices; if I’m working in prose, the limitations are the less rigorous impositions of the sentence and its syntax. I find that the limitations I impose upon myself are directly related to the discoveries I make. “Sky” felt immediately real to me because those discoveries felt new—to me and perhaps to others, too—and thus worth shaping and crafting. As far as possible, I try never to know what I’m going to write before I begin the process. So I guess, to (finally) answer your question: Though I must have been aching somewhere for people who have been lost, abused and abandoned as the woman in this poem is, the process itself was the poem’s inspiration. What compelled you to submit your work for this anthology? Was it a difficult decision? It’s been a while since I submitted the poem, but I suspect that, when I saw the call, I thought, maybe that “Sky” poem would sing for them. I’m glad it did, since at that point I had no idea whether the poem was any “good” or not—that is, I didn’t know whether it would communicate to someone other than myself. I don’t think it was a difficult decision, since part of the process of being a writer, and particularly a poet, is to send one’s work out into the world and hope it will make some connection. Of course it’s always gratifying to have one’s work accepted for publication; the difficulty, I think, comes with the fact that the majority of one’s poems—the vast majority, I think—will be turned down by prospective publishers, often many times. Every poet has experienced this, and it can be hard to believe in the value of one’s work, sometimes, in the face of that vast disinterest. So it takes a certain courage to submit! But as I said above, that’s integral to the process of writing with serious intent. Why did you choose this particular form or genre for this piece? Since I most often work in lyric poetry—that is to say, in small forms in which the line is determined by breath and cadence--it was natural for me to choose this form for the poem. Unlike many of my poems whose form is determined by a loose-form free verse, “Sky” is really a poem whose form was discovered in the breath, that is, in the rhythm of breath rather than heartbeat or some other more regular measure. This looser form allowed me to “leap” from scene to scene with greater ease than might have been possible had I used a tighter form, and I think (hope) it gave a certain openness to the poem’s overall feeling—particularly in the leap that leads to the last line. Can you speak to the evolution of writing your piece? How long did it take you to write this piece, including revision? As I remember, this poem came almost fully-formed in its first draft. Of course I revised, but that revision consisted mostly of listening carefully to the line breaks and the white spaces, to make sure I got the poem’s breath right, rather than the kind of “re-vision” in which the poem is cracked open and put back together in order to get to its marrow. To really read, really enter, any poem, one must breathe with the breath of the poet who wrote that poem. For the poet making a poem, capturing that breath can be an extremely difficult task, particularly in an open-form poem such as “Sky.” So part of the revision process consists of reading and rereading, listening carefully, making small adjustments and reading again—until all the moments in the poem are properly balanced and the marks that indicate that balance—line break, punctuation, white space—are organized precisely to hold the breath in place. As a writer, do you feel obliged to share difficult experiences? “Obliged” feels like the wrong word here, since I don’t feel “obliged” to do anything in writing except follow the paths that open themselves to me. Having said that, it’s a general understanding, I think, that writers and particularly poets are often drawn to writing precisely because difficult experiences have shaped a need to “say the unsayable,” to communicate what ultimately lies beyond language. I think this is largely true, certainly early in a writer’s development. And as I think more about your question, I realize that I can’t imagine a writer not drawn to exploring—and sharing--difficult experiences! The real question, I think, has to do with whether the writer locates herself only in her own difficult experiences or whether she’s able to find the means of opening herself to the suffering (and joys) of others. Perhaps a good writer starts in the first of these impulses and opens herself to the second. Furthermore, perhaps one quality we’re looking for in the best of writers is that empathic imagination by which the world is made larger. One wonders what discoveries we might make if we were able to open ourselves to the difficult experiences of all the world’s creatures, not only those of our fellow humans! What would you say to another writer who has been uncomfortable or silent about their experience? How can they begin to share their experiences? I think that a great deal of the best writing comes when a writer finds the courage to wrestle with those most uncomfortable of experiences. In fact, in many cases, that’s where we start; the very fact that one is drawn to writing brings music into that silence. I would try to get that uncomfortable writer to see that writing is a process of discovery, of digging deeper, and that by engaging in the process one might find a kind of healing, or at the very least a deeper response to that suffering, a way through it by digging down. I would also suggest that she find a community of other writers—people she trusts not to judge but to respond honestly—to read her work. Likewise, her response to the work of fellow writers drafts would empower her to greater confidence and sense of community. And the connection community provides—whether of friends, colleagues, fellow practitioners or readers whom we’ll never meet, is, after all, the point. Art makes the world larger to the extent that it forges community. How can a publication such as Grabbed help to empower or heal readers? The realization that we are not alone even in our aloness or solitude may itself be a source of healing. Reading about difficult experiences can be a source of greater empathy—toward others and toward oneself. Experiencing writers who have somehow found the courage to communicate difficult experiences in vivid, honest language, can give people the wherewithal to find that courage in themselves. On the most basic level, this act of sharing may give us the sense that we are less alone than we think. Again, it’s that sense of sharing and community. Michael Hettich was born in Brooklyn, NY, and grew up in New York City and its suburbs. He has lived in upstate New York, Colorado, Northern Florida, Vermont, Miami, and Black Mountain, North Carolina, where he now lives with his wife, Colleen. He has published over a dozen books of poetry and an equal number of chapbooks. His work has appeared widely in journals and anthologies. His most recent book of poems, To Start an Orchard, was published by Press 53 in 2019. Michael Hettich’s awards include several Florida Individual Artists Fellowships, a Florida Book Award, The Tampa Review Prize in Poetry, and the David Martinson–Meadow Hawk Prize, among others. He often collaborates with visual artists, musicians, and fellow writers. Hettich holds a Ph.D. in English and American literature from the University of Miami. For many years, he taught creative writing, composition and literature at Miami Dade College where he was honored with an Endowed Teaching Chair in Environmental Ethics. He has two grown children, Matthew and Caitlin, and a grandson, Owen Sharpe. His website is michaelhettich.com.

0 Comments

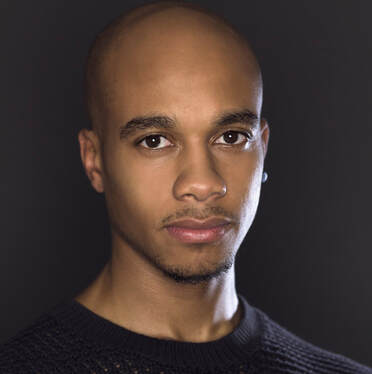

What is the name of the piece that you have in Grabbed? “One in Four.” What was the inspiration for your piece? What compelled you to write it? One in Four is an Irish charity that supports adults survivors of sexual abuse, offering legal advocacy and counselling services. This poem pays tribute to their amazing work. The name of the non-profit refers to a troubling statistic: According to an Irish Times article from 2018, “Current but outdated statistics state that one in four women and one in six men have experienced some form of sexual abuse.” Here is the link: The poem was part of a group of poems that I wrote between 2009 and 2012 and which was later published as a section of my first collection, Waiting for Saint Brendan and Other Poems (Salmon Poetry, 2012). Here is some background: In 2005, when I was 33, I started a counselling session by saying, “I think I was abused.” After the words left my mouth, it took seconds for almost 15 years of denial to crumble. I had always seen my “special friendship” with my abuser—a charismatic Benedictine monk / teacher from a prominent Sinn Féin family in Belfast—as “a relationship,” and “a romance,” and had hidden from myself the troubling and abusive aspects, of which there were many. (The grooming and abuse took place at an elite boarding school between 1989 and 1991 when I was 16-18). After reporting him to the school (he was “defrocked” / laicised by the Vatican and ejected from the school and the priesthood) and, later, facing the school in mediation, I used One in Four’s legal advice services to finally report him to the Irish police. Although the police were very supportive and presented a compelling book of evidence, along with my contemporaneous diaries detailing the abuse, The Director of Public Prosecution felt they did not have a case because, they said, I had “consented,” which is dark ironic. I was 16 when the grooming began, and just 17 when the physical part of it started, which was the age of consent at the time. I cannot help being left with the impression that the Irish legal establishment doesn’t understand how the grooming process works: how a young person is tricked into believing that it was something they initiated or wanted. What compelled you to submit your work for this anthology? Was it a difficult decision? If so or if not, why? Given the fact that the anthology is a #MeToo anthology, it felt appropriate to submit this poem, as it hinges on the lines “Until it can be said, / until I can say me too, / the crime will continue.” Was it a difficult decision? I think it is always difficult to make these experiences public, but it’s also important to step forward, both for myself and for others: as I say in the poem, “to hold space for those who can’t speak yet. / …Hold the line.” Here I’m thinking of the poetic line, but also of lines of battle. The line is formed by all those who have gone through this experience, but also all their allies; if they lock arms, then change will come. Why did you choose this particular form or genre for this piece? The subgenre of the book is, I think, located somewhere between confessional and neo-confessional modes: most of the poems follow Emily Dickinson’s suggestion to “tell the truth but tell it slant.” A lot of my poems about abuse in this book use metaphor to both protect the speaker but also to find an image that can give us greater access to an experience that is difficult to convey. However, this poem is more direct and political. Can you speak to the evolution of writing your piece? How long did it take you to write this piece, including revision? I can’t say how long it took me to write this specific poem. I think I wrote it quite quickly, perhaps in 2009 or so, and then revisited it while I was studying at NYU’s MFA in Creative Writing Program, where I received a lot of support from fellow students and teachers like Kimiko Hahn and Sharon Olds. I think it’s important to say that after I discovered I’d been sexually abused, it took me from 2005 until 2009 to write anything more than diary entries about those experiences, which constituted a form of Stockholm Syndrome (In Trauma and Recovery, Judith L. Herman talks about how sexual abuse can have much in common with the experience of being a hostage or a cult member, where the victim takes on the point of view of the abuser, which was true in my case. This kind of gas lighting constituted an abnegation of myself). Then between 2009-2012 or so, I started to find the images for it, and wrote around 40 poems about my experiences, some of which were published in the book. I don’t try to write about this subject or necessarily want to. It was forced upon me and I have to write it. That part of it can’t be changed, but I try to do something positive with the work and assist others. The activist part of it isn’t my goal at the moment of writing; but it is my goal at readings or when speaking about it. What do you feel the impact of the #MeToo movement has been on your work, if any? I think I experience #MeToo from the point of view of an ally. Although I have experienced sexual violence, given that this movement is about women who are speaking what has happened to them at the hands of men who attempted to silence them, I think it is important for men to be careful and sensitive and to not attempt to take centre stage. I could be wrong in this—perhaps I could have stepped forward in a more public way and found a more direct sense of community with other survivors, but I was burnt out after the various ways I had already fought my abuser and was trying to make living well my best revenge. Although he is not on a sex offender’s list, up to this point, I have unfortunately exhausted direct legal options. More ways might come through writing. Indeed, two-thirds of my next book, Crash Centre, is about the experience and is more direct than my first collection. Finally, I don’t think #MeToo has impacted my writing itself, but it certainly inspires me as a person and as a survivor. What would you say to another writer who has been uncomfortable or silent about their experience? How can they begin to share their experiences? All I can say is that writing about it for yourself (and / or for publication) can be very helpful and therapeutic. I would suggest seeing a therapist while accessing these experiences, and taking it slowly. My experience has been that writing about it one poem at a time is a healing process, though the healing can be fierce. At the time of writing I was often flooded with the past in a post traumatic sense, and was lucky to have a good therapist and a community of writer friends who were either doing something similar or who were open to my process. My goal in tackling the subject is to start from a (semi-) therapeutic place, and to end with a work of literature, hopefully! What was really helpful was, in each poem, to find an image to take me into and through. Here’s an example: for the poem “Great White Shark” in my first book, I started the draft with a found poem from a Wikipedia entry about the remora fish, the “sucker” fish that attaches itself to sharks. After leaving office hours with Kimiko Hahn, and her saying that the poem wasn’t fully alive yet, I found myself thinking and muttering, “I was your remora.” Although that line didn’t make it into the final version, it was the poem’s “through line”: the remora fish speaking to the Great White. In many ways I have found that imagery is, psychically and artistically, both the vehicle and the protection. Sharon Olds’ poem “Elder Sister” uses the image of the older sister as a dented shield, who protected her younger sibling from the worst of the abuse, even though they both endured it. For me, images are shields that have gone into battle with me and I won’t be setting them down any time soon. David McLoghlin is a poet and literary translator who lived in New York City between 2010 and 2020, where he attended New York University’s Creative Writing Program from 2010 to 2012. He has now relocated to his native Ireland with his wife and baby daughter. His books are Waiting for Saint Brendan and Other Poems (Salmon Poetry, 2012) and Santiago Sketches (Salmon Poetry, 2017), which is set entirely in Santiago de Compostela, Spain. Salmon will publish his third collection, “Crash Centre”, in 2021. His chapbooks are Sign Tongue, which won the Good Morning Menagerie Chapbook-in-Translation Prize in 2014, and The Magic Door (Blue Canary Press, Milwaukee, 1993). He is also one of three contributors to Suns, a chapbook of translations (Cardboard House Press, 2017). His writing has been broadcast on WNYC’s Radiolab, published extensively in journals like Poetry Ireland Review, Barrow Street and The Stinging Fly, and anthologised in Ireland and the USA. He has received prizes, grants and fellowships from the Sewanee Writers’ Conference, The Patrick Kavanagh Awards, New York University and Ireland’s Arts Council, has attended artists’ retreats at The Tyrone Guthrie Centre at Annaghmakerrig several times, and mentored and taught creative writing and literature at Sunken Garden Poetry Festival; University College, Dublin; New York University; Coler Specialty Hospital, and at Hunts Point Alliance for Children in the South Bronx, where he was Resident Writer. www.davidmcloghlin.com  What is the name of the piece that you have in Grabbed? “Found: Chorus to a Girl” What was the inspiration for your piece? What compelled you to write it? I’d watched videos responding to street harassment that turned the focus back to the bodies of the harassers. I didn’t want to do that in writing and tried to find another way to record my own experience of harassment (in many spaces). The words themselves were ugly, so I wrote down what had been said to me and worked from there. Why did you choose this particular form or genre for this piece? The prose poem feels less vulnerable to me than a poem with line breaks. It throws everything together. I think it shows how harassment accumulates in one person, erasing the individual and creating a spectre. Can you speak to the evolution of writing your piece? How long did it take you to write this piece, including revision? I wrote the first draft in 2014! I messed with the form, title, and transitions off and on over the years, but I didn’t add or take away much. As a writer, do you feel obliged to share difficult experiences? Why? I try not to feel obliged. But I do tend to write about what I’m thinking, and difficult experiences aren’t easy to stop thinking about. What would you say to another writer who has been uncomfortable or silent about their experience? How can they begin to share their experiences? All poems are just for yourself until you share them. Write notes. Write crappy drafts. Remember that writing doesn’t have to be confessional if that’s weighing you down. Read The Descent of Alette and come back. Holly Mitchell is a queer poet from Kentucky, now living in New York. A winner of an Amy Award from Poets & Writers and a Gertrude Claytor Prize from the Academy of American Poets, Holly received an MFA in Creative Writing from New York University and has poems in Baltimore Review, Juked, and Narrative, among other journals.  What was the inspiration for your piece? What compelled you to write it? I wrote “Cocoa Beach” about a frightening close call I had in my early 20s when a car full of men tried to abduct me. I never told anyone about it (not even my roommate that night) because I was deeply ashamed and thought it was my fault. I should not have dared to walk alone after dark, should not have assumed I had any right to safety as a woman. I tried to forget about the event, and when I read the poem now it seems almost as if it happened to someone else. I had come of age on an Air Force base in the California desert where it was so safe my girlfriends and I walked home from the teen center at midnight on Fridays and Saturdays. Rattlesnakes, not men, posed the only threat. Everything changed that night in Cocoa Beach. I realized in one blinding moment that I would never again be safe, that men would always hold the potential of danger, that I could never let my guard down. Why did you choose this particular form or genre for this piece? I’m a narrative poet, and it’s considered somewhat difficult to tell a story in a pantoum, but I like a challenge. I thought the form’s recurring lines and repetition could help me create the needed tension and allow me to fill in the story despite the fuzziness of many details decades later. It was painful to write because I experienced the fear again, but the puzzle-like challenge of the form itself provided the biggest obstacle. I revised it for about a year before I was satisfied, which is pretty fast for me. As a writer, do you feel obliged to share difficult experiences? Why? I don’t feel any obligation to write anything. I have found, though, that if I’m not tackling something I feel strongly about, I won’t have the stamina to work to perfect the poem and it will lack heart. So I try to be brave, go deep and be honest, no matter how painful it is. Otherwise, it’s not worth the effort. What would you say to another writer who has been uncomfortable or silent about their experience? How can they begin to share their experiences? I would encourage tentative writers to try not to worry about what anyone will think when they write, to turn off their internal censor, write the poem just for them and see where it takes them -- not every poem is successful anyway. If it’s strong, then they can decide if they should share it. It’s also useful to try “hiding” in a persona poem. Terry Godbey has published four poetry collections: Hold Still, finalist for the Main Street Rag Poetry Book Award; Beauty Lessons, winner of the Quercus Review Poetry Book Award; Behind Every Door, winner of the Slipstream Poetry Chapbook Contest; and Flame. A winner of the Rita Dove Poetry Award, she has published more than 150 poems in literary magazines and works as a freelance writer in Orlando, FL. Also a photographer, she wanders in woods and wetlands every chance she gets. See more of her writing and photos at www.terrygodbey.com.  What is the name of the piece that you have in Grabbed? Kidnapped Girls What was the inspiration for your piece? What compelled you to write it? I was inspired by the 2014 kidnapping of school girls in Nigeria by the terrorist group Boko Haram. I thought of the incident described in my poem, and of the book All I Really Need to Know I Learned in Kindergarten, and realized that the facts of life as a female in this world had always been clear to me. When I was in kindergarten, and the neighborhood boys formed gangs to sexually menace girls, this was simply what happened, with none of us kids knowing or questioning why. Luckily, it was harmless, literally only child’s play, but was our game some kind of inborn practice for the future? My grandmother seemed to think so. I saw what happened in Nigeria, what happens all over the world, as the adult version of my childhood experience, and wanted to convey that feeling. I have spent my life wondering, but still don’t know, why we played these games, where the idea came from. My grandmother only wanted to keep girls pure, free from pregnancy and shame, until they could be safely married. I was afraid of her anger as a child, but now saw her power to shout NO to sex in a new light. Saying no could be truly protective, not merely policing, of women. Used for the right purpose, a wrathful voice like Grandma’s could be used to shame rapists and kidnappers and should be. I wanted the force of her sound waves to be able to stop Boko Haram. What compelled you to submit your work for this anthology? Was it a difficult decision? The decision was not at all difficult. I learned of the anthology through my poetry teacher Ellen Bass and was happy to have the opportunity to submit. My poem had previously been accepted, but not yet published, by a wonderful journal which unfortunately had to cease publishing. When I heard of the Grabbed anthology I was excited to think my poem might find another poem there. It seemed like the perfect place. I was also thrilled that Joyce Maynard and my heroine Anita Hill were participating in the book. I was still burning about the Anita Hill hearings and ever will be. Why did you choose this particular form or genre for this piece? My first impulse is usually toward poetry. I like trying to say as much possible with the fewest words. That said, I also like attempting essays. Can you speak to the evolution of writing your piece? How long did it take you to write this piece, including revision? I was asked to do a partial revision by the editor of the journal that first accepted the poem. She helped me with the process. Later, I made a few more changes before submitting it to the anthology. So the whole process took several years, but was not continuous. As a writer, do you feel obliged to share difficult experiences? Why? Yes. Because the sound and light of words are needed to dispel the silence and darkness of secrecy and trauma. My poem in this anthology is more collective than personal in feeling, but I know how hard it can be to share experiences that are traumatic even to think about. Overcoming the resistance to re-experiencing the trauma becomes part of the difficulty of writing. What do you feel the impact of the #MeToo movement has been on your work, if any? The #MeToo movement has been yet another affirmation, and the strongest yet, of the universality of some of my/our experiences and their need to be shared to bring about collective change. I know from experience how long this can take. I read The Second Sex when I was twelve, came of age in the ‘60s, experienced second-wave feminism in the ‘70s, followed by Phyllis Schlafly and the sad recession of the wave, then a resurgence of the wave with the Anita Hill hearings, and now another with this movement. History progresses in waves and although our bodies don’t evolve, culture can. The struggle of women is as old as humanity, in part because for women to be free men must also be free. Unless that’s vice versa! Also, generations are short and much gets forgotten that must be rediscovered to be remembered. And youth thinks differently than age, yet age only makes me feel my youthful thoughts more deeply. If historical movements proceed in waves, participating in one as a writer is like helping to build a cathedral. My or your story may be remembered or it may not. But while it is read it has a chance to affect another life directly, and that is what builds the cathedral. Anyone who wants to tell a MeToo story should find a way to do it. The material will not be wasted. What would you say to another writer who has been uncomfortable or silent about their experience? How can they begin to share their experiences? Joining a writer’s group led by a skilled writer/teacher can be a great way to start sharing experiences safely. The leader should understand the nature of your experiences and the special difficulties of writing about them. All personal experiences are difficult to write about in a way that reaches the reader, but some more than others. Trauma is famous for wishing to stay hidden. If your experiences have been very traumatic, and you have not yet done so, you might also consider seeing a therapist. You can read books like Gregory Orr’s Poetry as Survival, Tillie Olsen’s Silences, Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own, to name some classics. There are many more. You can journal just for yourself and remember that you are not alone. This becomes evident as soon as you open your mouth. Others join you. But it does take courage to start. It is scary yet a privilege to be able to speak. We are lucky to have more opportunity now than ever before. How can a publication such as Grabbed help to empower or heal readers? By validating readers’ experiences. By showing readers they are part of an already huge and powerful crowd. By giving them permission to keep moving forward. Catherine Gonick’s poetry has appeared in literary magazines including Notre Dame Review, Beltway Poetry Quarterly, Lightwood, Forge, Sukoon, and PoetsArtists, and in anthologies including in plein air, and forthcoming, Poemas Antivirus. She was awarded the Ina Coolbrith Memorial Prize for Poetry and was a finalist in the National Ten-Minute Play Contest with the Actors Theatre of Louisville. She is part of a company that mitigates the effects of climate change.  What is the name of the piece that you have in Grabbed? Blindsided Can you speak to the evolution of writing your piece? I have been writing about sexual abuse for decades –sexual harassment in the workplace, violence against women in film, forced childbirth, sexual abuse and assault across religious denominations, especially in the church of my childhood, the Catholic Church. I’ve written and published many personal essays--about having had breast cancer, struggling with an eating disorder, the impact of the Catholic Church’s misogyny on my sense of self, my sexuality, my body. But not until publishing my essay “Blindsided” in Grabbed have I revealed this experience of sexual assault and its aftermath. “Blindsided” is excerpted from a collection of essays, a memoir in progress about my awakening as an Italian-American, working-class, second-wave feminist. The piece is neither new nor newly written. But the experience of seeing it out there in the world is new. Unlike my journalism and other personal essays, this essay represents a different order of revelation and vulnerability. While recalling the experience that is the subject of this essay has always stirred shock, bewilderment, and anger in me, not until I saw “Blindsided” in this collection did I feel what I have never really felt before—sadness. It is a deep, universal sadness, a sadness that very much matches the moment, when at last, the larger culture is willing to acknowledge the harm done, which is the only way that change will ever come. What would you say to another writer who has been uncomfortable or silent about their experience? How can they begin to share their experiences? For anyone who has been grabbed, assaulted, raped, or abused and kept that locked inside, please talk to someone you trust. Share the experience. Work through it. Don’t be afraid of it. By all means, write about it. But as to publishing your experience, I do not think that is an action best done on impulse. Let the idea of going public germinate. That’s not because you should not publish your experience, not at all. It is because you cannot predict the response. Not everyone in your world—family, friends, colleagues, strangers--may support you. You need to be prepared, to know where you will go for solace and comfort. But if you do find the courage to share what happened, know that you will be helping to decimate the notion of the ordinariness of being “grabbed.” You will be helping to end the shame heaped upon the targets of that abuse instead of on the perpetrators. And your voice will be part of a growing worldwide chorus—you will not be alone. How can a publication such as Grabbed help to empower or heal readers? The sheer volume and power of the voices in this unique anthology provide a dramatic example of how normalized both sexual assault and the silence surrounding sexual assault have been in American culture, and how crucial it is that the normalization and the silence end, not just in the U.S., but all over the world. Angela Bonavoglia, MSW, writes about social, health and women’s issues, politics, film, TV, and all things Catholic. Most recently, she authored Good Catholic Girls: How Women Are Leading the Fight to Change the Church (a Booklist Nonfiction Women’s History Top 10, 2006). Her first book, The Choices We Made: 25 Women and Men Speak Out About Abortion (foreword by Gloria Steinem) features her interviews with celebrities and other prominent people about their abortion experiences (1920s-1980s). Her work has appeared in many venues, including Ms., The Nation, the Chicago Tribune, Salon, Women’s Media Center, Rewire, Medium, and HuffPost. Find her on Twitter @angiebona or at www.angelabonavoglia.com.  What is the name of the piece that you have in Grabbed? “When a White Man Attempts to Steal Your Soul” What was the inspiration for your piece? What compelled you to write it? Back when I used to be a regular at the gym (and, as much as I’d love to blame the fact of COVID making gyms untenable for that no longer being the case, my therapist says being honest about my choices is a great way to combat imposter syndrome), this fascinating thing would happen whenever I entered the steam room. Pretty consistently—and I’m sure this was partly only so consistent because of the specific gyms I frequented (in queer-friendly neighborhoods of New York City)—there’d be a guy or a few lounging inside, cruising for a sexual encounter with someone they didn’t know. I didn’t really have a problem with this so long as consent and boundaries were acknowledged and respected. When they are, the person being cruised usually only notices what’s happening if they are also looking for the encounter—if they return the cruiser’s sideways glance that’s held for mere moments too long, or if they refuse to slide away down the damp wooden bench when the cruiser sits just close enough that the hairs on their legs come within a moth’s sigh of grazing. When consent and boundaries are not respected, however, there is no way not to notice, even if you’re just trying to sweat out the tension after backbreaking exercise. Even if you’re straight. Even if you’re too young. And, unfortunately, this happened far too often, and was the same type of violence even if I was open to a different kind of sexual experience with a different kind of person at the time. I noticed this happening particularly when the cruiser was an older white man. He would usually spend all day in the steam room, a venus fly trap just waiting for his prey. The clientele of the gyms I visited were primarily Black, just like me. I would become so furious when this happened—even if it wasn’t directed at me. It evoked all of the sexual violence I experienced since I was a ten year old boy, violence I no longer questioned as being violence, though it took many years for this type of clarity (shout out again to my therapist). Just like the child I used to be, I always felt so powerless in the face of these steam room predators. All the solutions I could think of always felt wrong. As a Black person, I knew I couldn’t turn to the police and expect them to believe my word over theirs, what to speak of expecting law enforcement to have a response that wasn’t carceral, when carcerality is so central to the pervasiveness of sexual violence in this society in the first place. But it was either the police, running away, or responding the violence myself, which felt equally out of the question, though I didn’t know why. Or rather, the reasons why—that violence is never the answer, that these are things police are supposed to handle—felt woefully inadequate. This essay was me exploring whether those reasons for inaction actually hold up under scrutiny. When, if ever, is a survivor’s violent response to sexual abuse justified? What happens when we allow that there must be a point when it is? How do the answers to these questions intersect with the history of racial and gender-based oppression, and what responses are deemed appropriate to those things as well? Can you speak to the evolution of writing your piece? How long did it take you to write this piece, including revision? I had the idea to write the piece after one particularly disgusting experience where I literally had flashes of myself killing the predator in the steam room, but instead I just walked out. In the face of this inadequate response, my body retaliated, and I nearly had a panic attack on the walk home. I process my social anxiety through my writing, and writing through what was happening to me and trying to make sense of it felt natural. I pitched the piece to a friend who worked as a junior editor at a fairly well-known literary magazine, and she loved it. The first draft I sent her was admittedly awful. I was still trying not to say what I knew needed to be said, what my panic-stricken body was telling me that I really wanted to say, but my friend was so gentle and sensitive, which I so appreciate. She asked to get coffee to talk about revisions, encouraged me to push further into my honest feelings and away from vague generalities and cliches around sexual violence I’d ran away into, and eventually I got closer to a piece that felt honest and truthful. At that point—and, I would say, relatedly—my friend couldn’t get approval for publication from her bosses, and she eventually killed the piece. Usually, the things that ease my anxieties, especially around issues like sexual violence, are the same things others find inconceivable. I did some more revisions and then pitched it to an editor at the New York Times, who really liked it as well. I had never written for the publication before, and it was such a different process than what I was used to. After her initial interest, I would follow up every few weeks and she would let me know she was still trying to find a date for it. After about two months, she admitted that she didn’t think she’d ultimately be able to get approval to publish either. Finally, I pitched it to the (now defunct) queer publication, INTO, and they ran it pretty much as was. This was about six months after I started the piece. It’s important to note that all the editors who showed initial interest were Black, but only at INTO did the Black editor have final say. It’s important because, if violence in response to oppression is on the table, non-Black people have much more at stake. When Richard Blanco’s people reached out to my agent about Grabbed, submitting the piece made sense. The project seemed guided by a credo of the importance of uncomfortable truths in the face of sexual violence—a credo that isn’t widely shared in a patriarchal society, but that is necessary. I’m so glad the piece ultimately found a home here. As a writer, do you feel obliged to share difficult experiences? Why? I feel obliged to share difficult experiences only in the sense that, usually, writing through difficulties is how I find the answers I’m seeking. When people ask for whom I am writing, the answer is almost always “me.” That’s not to say that I don’t consider anyone else’s perspective, or that I write things like this without any concern for helping other people. But I have found that the best I can do for others always comes from knowing myself, knowing my limitations, strengths and weaknesses; and the best way I can come to know myself is by writing honestly to myself and sharing that writing with others whom it can possibly help too. But it’s not for (or only for) others. That distinction is important because when you feel obligated to write for others only, or even centrally, you can sacrifice yourself in ways that are detrimental to everyone. You write about things you have no expertise or investment in. You don’t find the answers you are looking for because it’s not about what you are looking for at all. You make yourself vulnerable to horrible things without any necessary protections in place. So, I’d like to think I wouldn’t have ever written something this difficult until I was ready for it. Until I knew what answers I was seeking and until I had the weapons to make the journey to them safely. By the time the piece was rejected, I was completely okay with that. I did not question its usefulness or my skills. Because I didn’t feel obligated to the people who made those decisions, or anyone who might share their judgment. What would you say to another writer who has been uncomfortable or silent about their experience? How can they begin to share their experiences? I would reiterate what I said above: share your experience for yourself. You have a right to find the answers you are seeking, even if it makes others uncomfortable, but you do not have to pretend to have the answers if you don’t, if it makes you unsafe. I would share what my therapist taught me: being honest about your choices is a great way to manage your anxieties. Everybody is not going to like you sharing your truth, but those who are supposed to hear it will. Everybody won’t think it’s publishable, but those who know better exist. Do it with them in mind. There are so many more of us than they make it seem. Writing for yourself, and others like you, is okay, is worthy, is a glorious thing. And that is because you are a glorious thing. Hari Ziyad is a cultural critic, a screenwriter, the editor-in-chief of RaceBaitr, and the author of Black Boy Out of Time. They are a 2021 Lambda Literary Fellow, and their writing has been featured in BuzzFeed, Out, the Guardian, Paste magazine, and the academic journal Critical Ethnic Studies, among other publications. Previously they were the managing editor of the Black Youth Project and a script consultant on the television series David Makes Man. Hari spends their all-too-rare free time trying to get their friends to give the latest generation of R & B starlets a chance and attempting to entertain their always very unbothered pit bull mix, Khione. For more information about the author, visit www.hariziyad.com.  What is the name of the piece that you have in Grabbed? “Hitchhiker” What was the inspiration for your piece? What compelled you to write it? It’s odd to think of trauma as inspiration, but humans have been using art, whether it’s music or painting or the written word, since the beginning to tell stories about their lives. I survived what could have been a fatal attack. I buried the incident for decades. Poetry offered me a way to control the narrative, to transform the trauma into something new, outside of myself. What compelled you to submit your work for this anthology? Was it a difficult decision? I had already submitted this poem a few places and had it rejected. I was happy when it found a home in Grabbed. To be part of a community, to reach readers in a meaningful way is important. For other survivors of sexual assault, and for a larger audience. Sexual violence is all about power and silencing. The more we speak out, the more we reclaim our power. Why did you choose this particular form or genre for this piece? The main reason is that I’m a poet, not a writer of memoir or fiction. I like the freedom that poetry gives me. Compression, wielding of imagery and metaphor—these are tools for turning thought, feeling, and memory into the lyric. Can you speak to the evolution of writing your piece? How long did it take you to write this piece, including revision? It took me 30 years before I tried to write about what happened to me. And even then, it wasn’t until I read a poem by Charles Rafferty that I was able to find a way in. It’s often good practice to model a poem on someone else’s. In this case, it afforded me a certain distance from the material. As a writer, do you feel obliged to share difficult experiences? I’m not sure “share” is exactly the word. I think writing, poetry in particular, gives us the opportunity to transform our experiences, and ideally, ourselves. I agree with the poet Gregory Orr who says, “I believe in poetry as a way of surviving the emotional chaos, spiritual confusions, and traumatic events that come with being alive.” What do you feel the impact of the #MeToo movement has been on your work, if any? I think the outpouring of stories, of voices, has given me a feeling of validation, a recognition that my experience matters, that it’s a piece of a bigger story. What would you say to another writer who has been uncomfortable or silent about their experience? How can they begin to share their experiences? Again, maybe “share” isn’t exactly the word. What writing affords, particularly forms like poetry and fiction, is a way to take the raw material of one’s life and turn it into something powerful or beautiful or comical or satirical, even all of those things at once. And that is what is shared with the reader. It is still a vulnerable act. I think getting distance is helpful, whether it’s time or writing in the third person or in the voice of a fictional character. For me, the key is taking control of the narrative. How can a publication such as Grabbed help to empower or heal readers? Knowing one isn’t alone is very healing. Witnessing others speak out about their experiences, turn them into art, can be an inspiration. As I mentioned, sexual violence is a kind of silencing. Anthologies like Grabbed are the opposite of silence. Cynthia White’s poems have appeared in Massachusetts Review, Narrative, ZYZZYVA, Grist, and Catamaran among others. She was a finalist for Nimrod’s Pablo Neruda Prize as well as New Letter’s Patricia Cleary Prize, and was the winner of the Julia Darling Memorial Prize from Kallisto Gaia Press. She lives in Santa Cruz, California.  What is the name of the piece that you have in Grabbed? A Brief History in Pink What was the inspiration for your piece? What compelled you to write it? An incredible conversation with Robert Hass at the Miami Book Fair, my own weariness with overt and covert homophobia, allies in private talking as if we were vermin, the pendulum swing of folks succumbing to compassion fatigue as they tire of political correctness, four months of nightmares preceding my lover’s death, a perfect storm of disgust, disappointment, anger, and grief. What compelled you to submit your work for this anthology? Was it a difficult decision? I am, in general, oblivious to publishing opportunities. I used a submission service for a while otherwise I’d have even fewer publishing credits. A trusted friend requested that I send some work. I don’t think I understood the magnitude of the Anthology’s undertaking at the time. It is much bigger than I could have imagined. Had I known then, I probably would have fearfully begged off. Why did you choose this particular form or genre for this piece? It’s a performance piece. A bit of psychodrama. Initially I spread it out over multiple columns and pages with a whole lot of space but that’s not true to the feeling of the piece especially after some drastic cuts (approx one third of the poem). It became a claustrophobic piece and that led to its final utilitarian form. I can’t wait to make the video; it will probably need a seizure warning. Can you speak to the evolution of writing your piece? How long did it take you to write this piece, including revision? Sometimes a rant writes itself. Or seems to. The words and feelings behind them get dammed up until they explode out into the world, a bit like projectile vomiting and possibly in the first draft more therapeutic to the writer than to the reader. The clichéd answer is it took however many years I was old at the time. I don’t fully know how to describe being queer and long term positive in a straight world. I don’t want to demonize the masses but the constant micro and macroaggressions are wearing. I didn’t start the piece with a destination in mind but when the first line wrote itself I knew I was in for a ride. Sometimes large events are like planets that pull everything around themselves into orbit. I’ve been writing AIDS elegies for decades but I couldn’t write a Laramie or a Pulse Nightclub poem, but it turned out I needed to, I needed to mourn the fear and hatred in this world and its many casualties. My lover was shot and killed in March of 2018, I have a memories of him dancing in pink knee high sneakers. He certainly informed this piece but I made him wait for a different poem or two of his own. Revision took the longest, editing for presentation and flow. The poem had a whole other section where the narrator was, in a forced and desperate way, grasping at some sort of peaceful resolution. It stank like the lying, rotting, lifeless thing it was, and eventually I lopped it off in its entirety. Often, editing the line between hope and wishful thinking is the hardest cut for me. One of my personalities is a Goth Pollyanna, but she’s not an accomplished writer. I toyed with cutting some of the more nerdy parts but I am and hope to always be true to my nerd self. I’d love to write a hopeful companion piece, but, now that the Deplorables the world over have shown their hand, I have to figure out how without lying to myself. As a writer, do you feel obliged to share difficult experiences? Yes, definitely. When I was very young I grew up believing that everyone’s life was just like mine. There was the public life with the pretense of “normalcy”, and the private where the threat of physical, emotional, and sexual abuse was a given. Imagine my surprise when I heard and believed the replacement lie: no, this is not universal, this only happens in your house. Abuse thrives in secrecy, isolation, and silence. When I first began writing, I wrote rants and Creative Writing tried its best to suppress that. Just like the home rule of not airing dirty laundry, I was taught to write around trauma, hint at it without calling it out, and move on. Hearing Sharon Olds and Patricia Smith perform live at the first Palm Beach Poetry Festival in 2005 brought me back to my initial writing instincts: expose everything, whoever didn’t want it told shouldn’t have done it, condoned it, or tried to ignore it. Housman echoes the book of Job when he quotes “when your soul is in my soul’s stead.” Even when I was talking around issues I could recognize the person in the audience that fully understood. There is always someone else out there who needs to know that they are not alone. That was true about coming out as queer, as abused, as positive. We don’t need to be ashamed or face it alone. People performing hateful acts need to know that the protection of silence will henceforth be denied. Poets are prophets. Silence=Complicity, Silence=Death. What do you feel the impact of the #MeToo movement has been on your work, if any? Conversation matters. Public discourse matters. When clergy abuse took hold of the national media in the 90s, I found myself crying over the news reports. I needed to write about the constant threat of sexual abuse from the priests and upper classmen during my school days and about systemic schizophrenic hypocrisy. Without the #MeToo movement I don’t think it would have occurred to me to write a poem about being drugged and raped in my early twenties. Growing up around abuse, the rape just seemed like more of the same. At the time, I blamed myself for letting my guard down, and then stuffed the whole experience. Guys don’t get raped, I told myself. Years later near the end of a long term relationship that was dying in part from my partner’s drug addictions I was reminded, oh yes they do. What would you say to another writer who has been uncomfortable or silent about their experience? How can they begin to share their experiences? I have a dear friend who complains about shock poetry, the final line always the coup de grace. It is so tempting for anyone who has been traumatized to write that poem. Processing trauma was where I learned the difference between what I had to write (purge) and what I had to perform. Every writer has to find their own way. That’s what writing is. I had to start with the bare narrative, just the facts, no artifice or ornamentation. For years that’s where I left it. Therapy helped. Writing helped. Eventually I mined my therapeutic purges for my performable art, my first erasures. Patricia Smith shows an amazing matter of fact method of putting the trauma out there in “When the Burning Begins.” In Cenzontle Marcello Hernandez Castillo introduces Daisy, the belt used to beat him, as a recurring character in “Sugar” and other poems. In The Tradition, Jericho Brown addresses rape from a distance in “Ganymede” as well as the comingling of love and abuse in “Prayer of the Backhanded” from Please, as does the amazing Sharon Olds in countless poems. Any on them can serve as an example of where to begin. What else do I say to any other writer? First, save your life. Then excise the tumor as best you can with whatever help you can. Then decide what to do with it. It’s difficult and tearful work but it’s a path toward freedom. Through it all, be kind to yourself. How can a publication such as Grabbed help to empower or heal readers? Children of abuse live in fear, that is our baseline state, and no matter what age the abuse happened there is still part of us that experiences it as a child. The knowledge that we are not alone, that there are others who endured similar or worse, others who just might understand, others who found a way to live and love their life, is a powerful step toward healing. Giving voice to whatever seems too difficult to express is what art does best. Giving ourselves permission to voice it, is an empowering step toward the freedom of healing. Michael Mackin O'Mara is managing editor and co-publisher of SoFloPoJo (the South Florida Poetry Journal), and has been published in Evening Street Review, Visitant, fields magazine, The Body, The Complete HIV/AIDS Resource, and Indolent Book’s HIV Here and Now Project among others. www.michaelmackinomara.com  What is the name of the piece that you have in Grabbed? The Worlds Words Make What was the inspiration for your piece? What compelled you to write it? My piece began with a completely different start, intent, and story. It started as a piece about the day when I was 7 or so and I was sat down to listen to a Bill Cosby stand-up album in someone’s kitchen to keep me busy while my mom was visiting there. I didn’t yet know that there was such a thing as stand-up comedy, and that it was meant for laughing. Sitting there at that kitchen table, I didn’t want to be rude by laughing out loud, and so I suppressed all my laughter while I waited for my mom. Ultimately, the piece was meant to talk about reconciling that memory of innocence with what we know of Cosby now. But as I started to recount the Cosby anecdote for Grabbed, I started to remember other instances of innocence pierced—instances that started at around the same time as that evening I listened to stand-up—and that led to the piece as it is now: an enumeration of all the transgressions and aggressions I’ve endured. (I’ve since remembered a few other encounters that were missed in the count.) What compelled you to submit your work for this anthology? Was it a difficult decision? If so or if not, why? A lot of my art production is auto-biographical in some way—films; photography; composite work—and so I didn’t give my piece for Grabbed particular thought in terms of exactly what I was writing about. It was only later that I realized I was exposing something about myself that almost no one is aware of, and I began to feel self-conscious about the disclosures. (I still haven’t decided if I’m going to tell colleagues at work about the book. Sorry.) Why did you choose this particular form or genre for this piece? The 1st person present tense took over early on. The dispassionate tone, stark and almost dissociative, very much mimics the way these memories play out in my head, still today. Listing the incidents across decades struck me as effective in conveying the ubiquity, variety, and ceaseless nature of unwanted sexual attention, aggression, and abuse. As a writer, do you feel obliged to share difficult experiences? I don’t feel obliged to share difficult experiences—but I happen to gravitate to the personal in my work. I think it’s important for people to name the unnamed, to bring into the light all that’s cloaked. Keeping things in the dark is very convenient for abusers, and for those who remain attached to juvenile ideals about the world and the people in it. Culture and society won’t shift consciousness, policy, and budget allocations until there’s enough of a groundswell on issues that it’s no longer tenable to deny what is. Artists tend to lead the pack when it comes to talking about the uncomfortable, and from there, eventually, it moves to the centre. (It’s not always and only artists, but they’re often in the first mix.) What do you feel the impact of the #MeToo movement has been on your work, if any? When #MeToo hit the scene, I felt it personally, coming out for the first time and adding myself to those who posted it on my social media walls. Since writing my piece for Grabbed, however, I notice the impact more in my daily life than in my work. I notice more than usual all the ways men take liberties; I notice more than usual all the social conditioning. What would you say to another writer who has been uncomfortable or silent about their experience? How can they begin to share their experiences? It’s not my place to make recommendations to other artists about what they address in their work. This is especially true in the sensitive matter of sexual assault and its continuum of behaviours. I would, in fact, be more inclined to recommend counselling before I would recommend making art about such a thing. How can a publication such as Grabbed help to empower or heal readers? Knowing we’re not alone in our experiences is huge. And to see a compendium of thoughtful, brave work on the topic, and in such volume, is a true testament to the fact that none of us are alone in our experiences of sexual assault. I hope Grabbed readers who themselves are survivors absorb this knowledge as a form of companionship and solidarity, and, ultimately, feel themselves to be part of a collective sovereignty; I hope the other readers gain insight into the impacts of sexual assault, grasp the pervasiveness of the issue, and come to understand its intrinsic ties to the failed social project called patriarchy, and its spawn, misogyny. Zoe Welch is a photo-based artist and writer. Her poetry and photographic work have appeared in the French Canadian publications Ciel Variable and La Revue des Animaux; her film Landing: le film pour Loïc was part of the National Film Board of Canada’s program on love that was presented at La Cinémathèque québécoise where the film is now also part of the digital collection; and she contributed a written piece to the anthology and New York Times bestseller, Women in Clothes. Her public art has been presented in Seattle as part of King County’s City Panorama program in conjunction with the Photographic Center Northwest; in Miami as part of #project305 in conjunction with the New World Symphony; and as part of the New York City Tree Alphabet project. In her current work, Zoe is examining what it means to live in US, where she moved in 2016. She’s the museum educator at The Wolfsonian – FIU where she leads K-12 and youth & programming. |

Grabbed BlogHave a blog idea for us? Submit it here. Archives

October 2020

Categories |

|

BUY GRABBED

|

If you or anyone you know is a victim of domestic violence, please call The National Domestic Violence Hotline: 1-800-799-7233 1-800-787-3224 (TTY) En Español: 1.800.799.7233 |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed